Dungeon Crawl Classics: Designing Old-School.

A design delve into the cult classic rpg of sword-and-sorcery.

A quick detour to “Ecstatic Truth.”

Excuse me while I nerd out. If you’re a film freak, you’ve likely heard of Werner Herzog and his “ecstatic truth,” his infamous answer to common criticism of his documentaries, and the overall direction of modern filmmaking.

If you don’t who what I’m talking about: Werner Herzog is a fatalist German director, writer, and artist. He’s a man who has made it his career being as close as possible to violence, dread, and tragedy. In his documentaries, this puts him in the narrative. Sometimes as one of its primary characters. He’s also known to heighten or accentuate scenes in a documentary, from rearranging elements in the frame, to giving instructions to the subjects on what to say and do.

To the documentary purist, this is heretical to what documentaries are. It crosses the line of an outside observer and recorder and turns the documentary into one with an authorial goal.

I think the idea of an objective or true story in documentaries is absurd. Impossible. The existence of the film crew, the knowledge that a documentary is happening, and the necessity to pick and edit footage means presenting a documentary as objective and “truth” is inherently dishonest.

What is ecstatic truth? The answer, to oversimplify, is emotional truth. This is what makes Werner Herzog famous. How war, death, and nature feels is hard to convey in “objective” camera framing. Footage from WWII, for example, feels plain, quaint, and sterile. A plane smokes, burns, and crashes. It all feels real, informative, and historic. But is that what you should feel? A man was in that plane. It caught fire and exploded. His friends watched him burn. Life and death with more death on the way. Did the camera capture the truth? Or was the dry empty feeling it gave you—in its own way—false, or worse, immoral?

Ecstatic truth is when fiction recreates emotional truth. In many ways, Saving Private Ryan is realer than footage of D-Day. Biopics are realer than a wikipedia entry. And in the case of Werner Herzog, his documentaries are truer than the documentaries made by his colleagues. His use of music, narration, and direction hones what’s dulled by the screen. In the absence of being there, or being the subject, ecstatic truth fills the humanist void.

What’s a design delve?

This is a design delve. A long and winding stair from a game’s mechanical rules all the way down to the fonts and paperweights. Dungeon Crawl Classics is huge. Unlike other games I’ve analyzed, this one demands we stay top-level, lest we get stuck = deep in its dungeons.

Introducing Dungeon Crawl Classics.

Talking about Dungeon Crawl Classics is like performing Stomp the Musical in a room full of bear traps. Talking about it means discussing Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, the Old School Revival, pulp fantasy, and my relationship to it.

All of these things are “cans of worms.” More importantly, they’re impossible to resolve. There is scarcely a word, idea, or concept in old-school gaming that isn’t contested. And here’s why: it’s all messy.

Dungeon Crawl Classics is the undisputed king of mess.

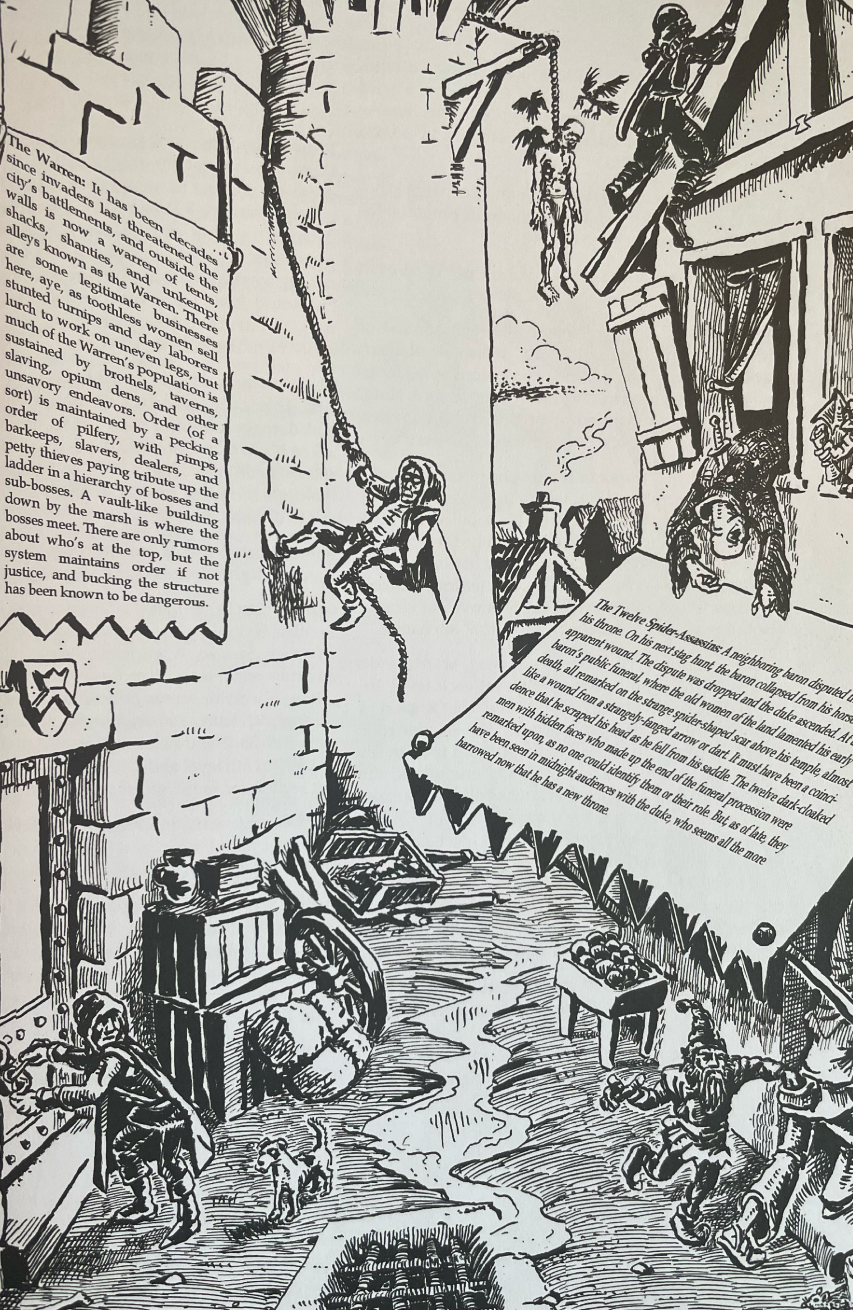

The infamous tome sags like a rack of ribs. The text is dense, the art is cornball, the rules are obtuse, and its ink-heavy maps drain printers like a lich at a baby shower. Fresh off the press, it looks like it was pried from a van with shag carpet.

Dungeon Crawl Classics is a gonzo bundle of extremes. It’s a speeding train of disco balls and kerosene—the Nic Cage of RPGs. You can’t look away, and you shouldn’t, because it’s doing something special.

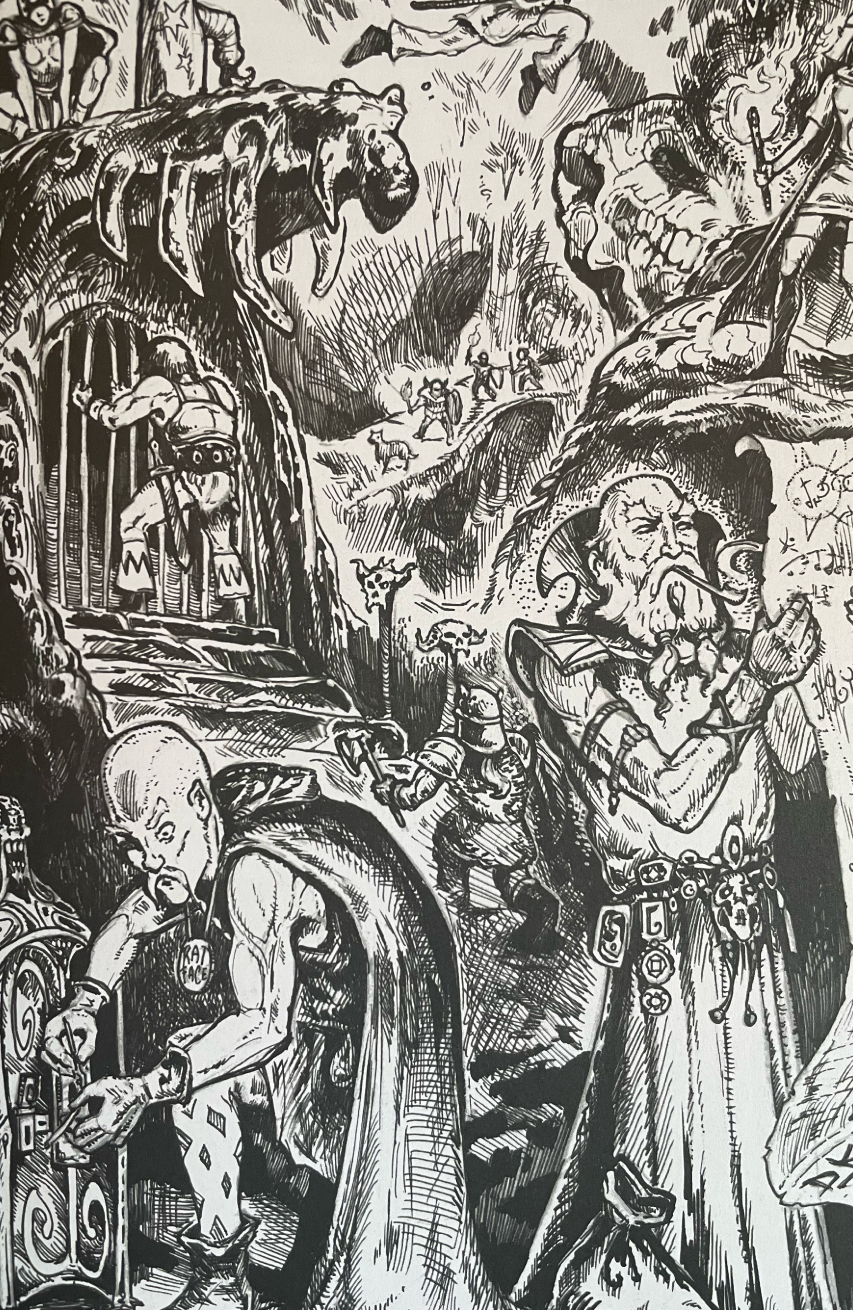

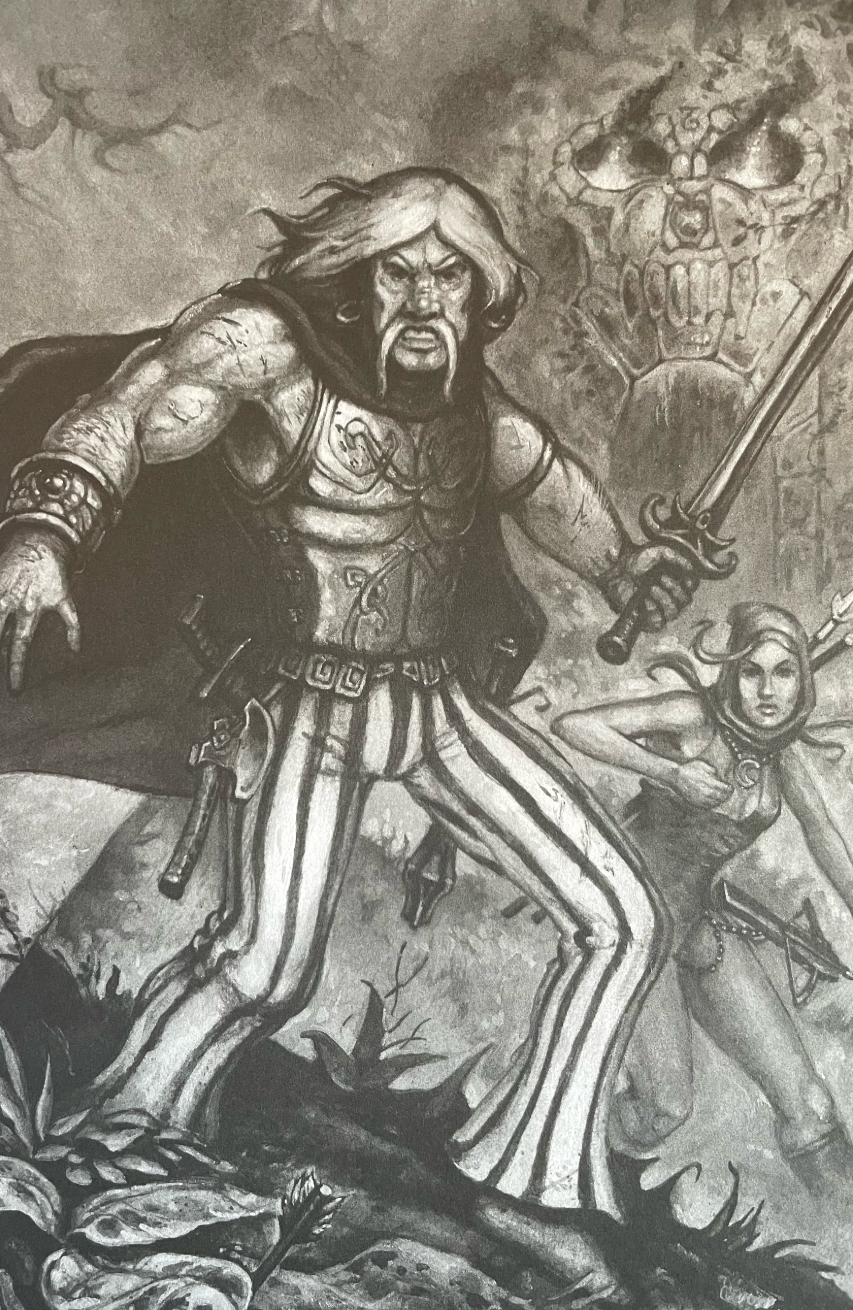

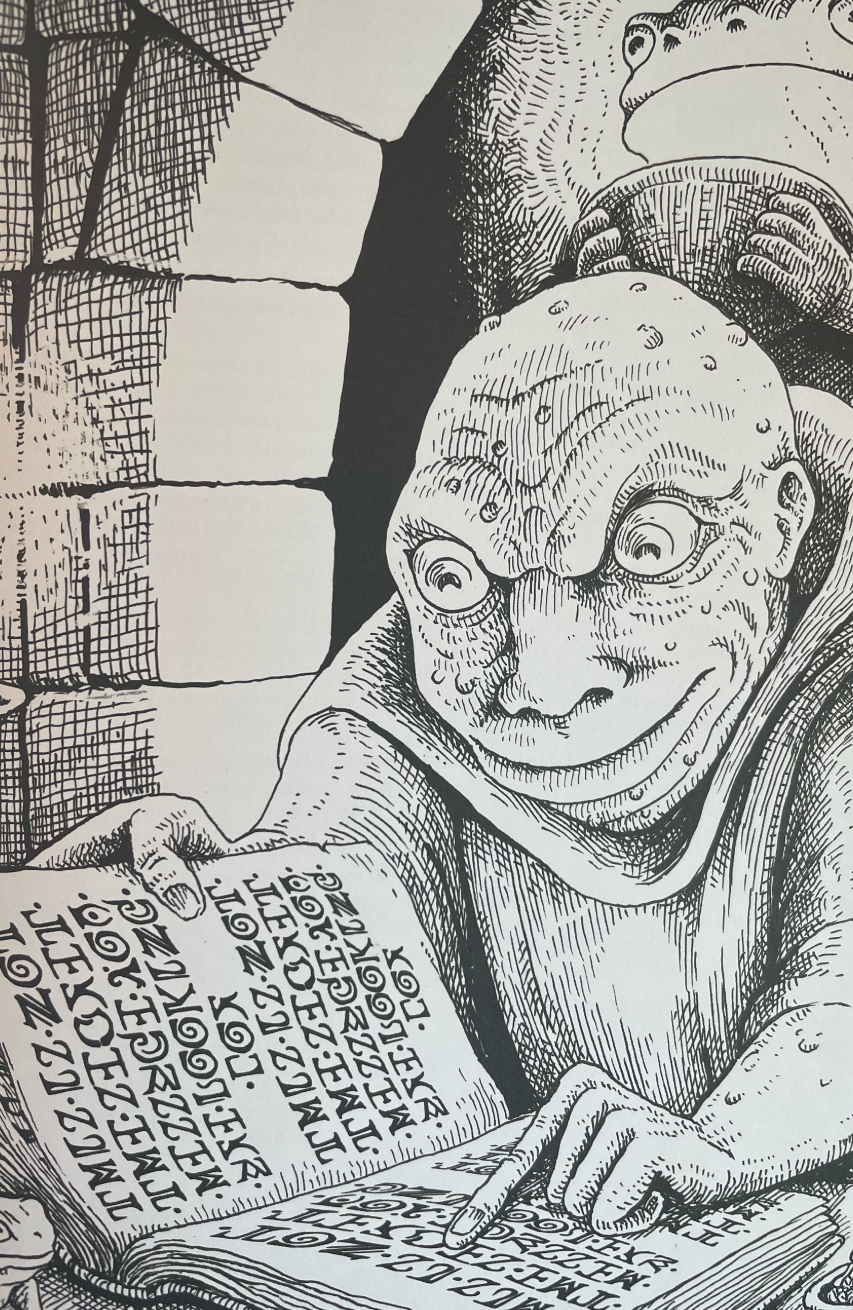

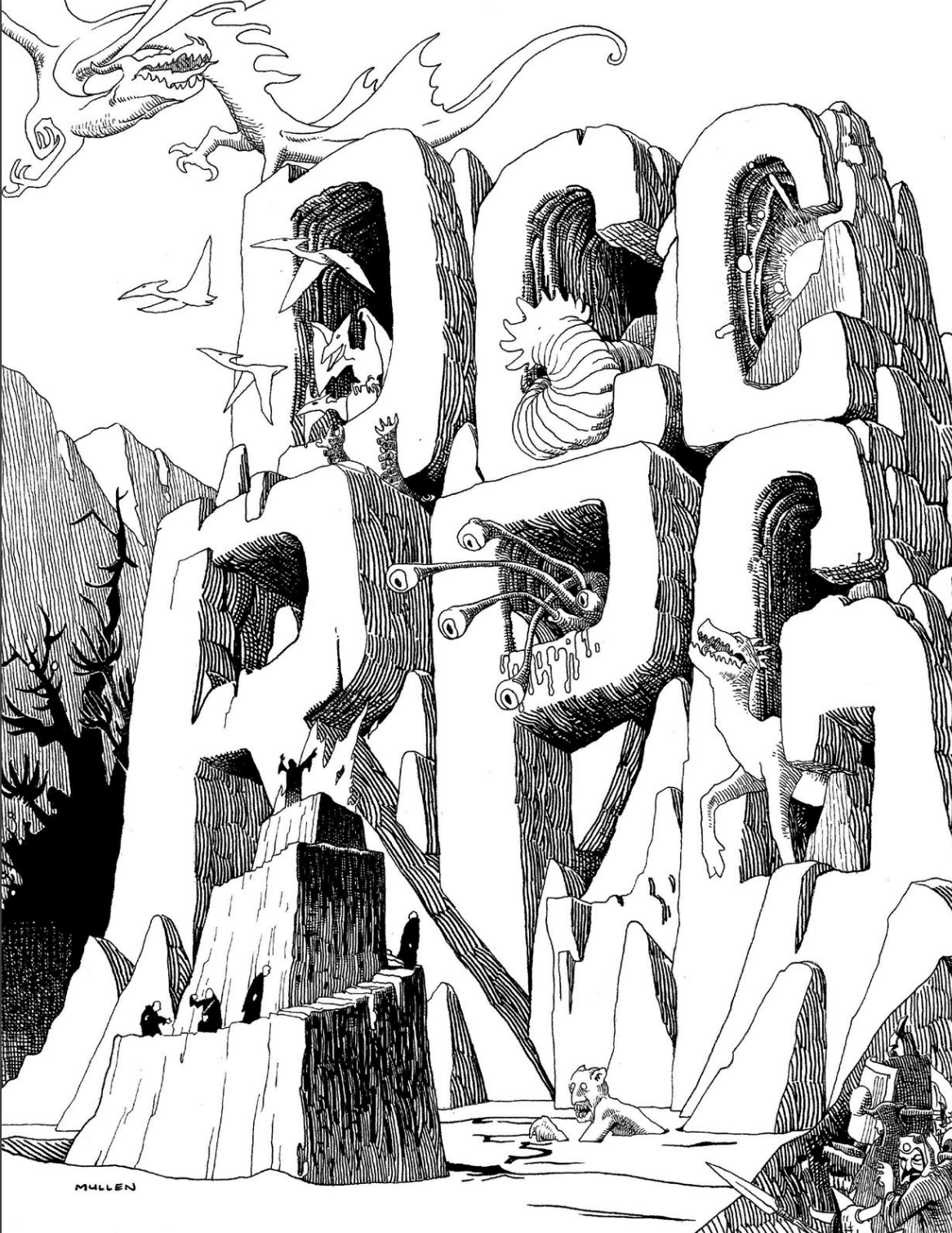

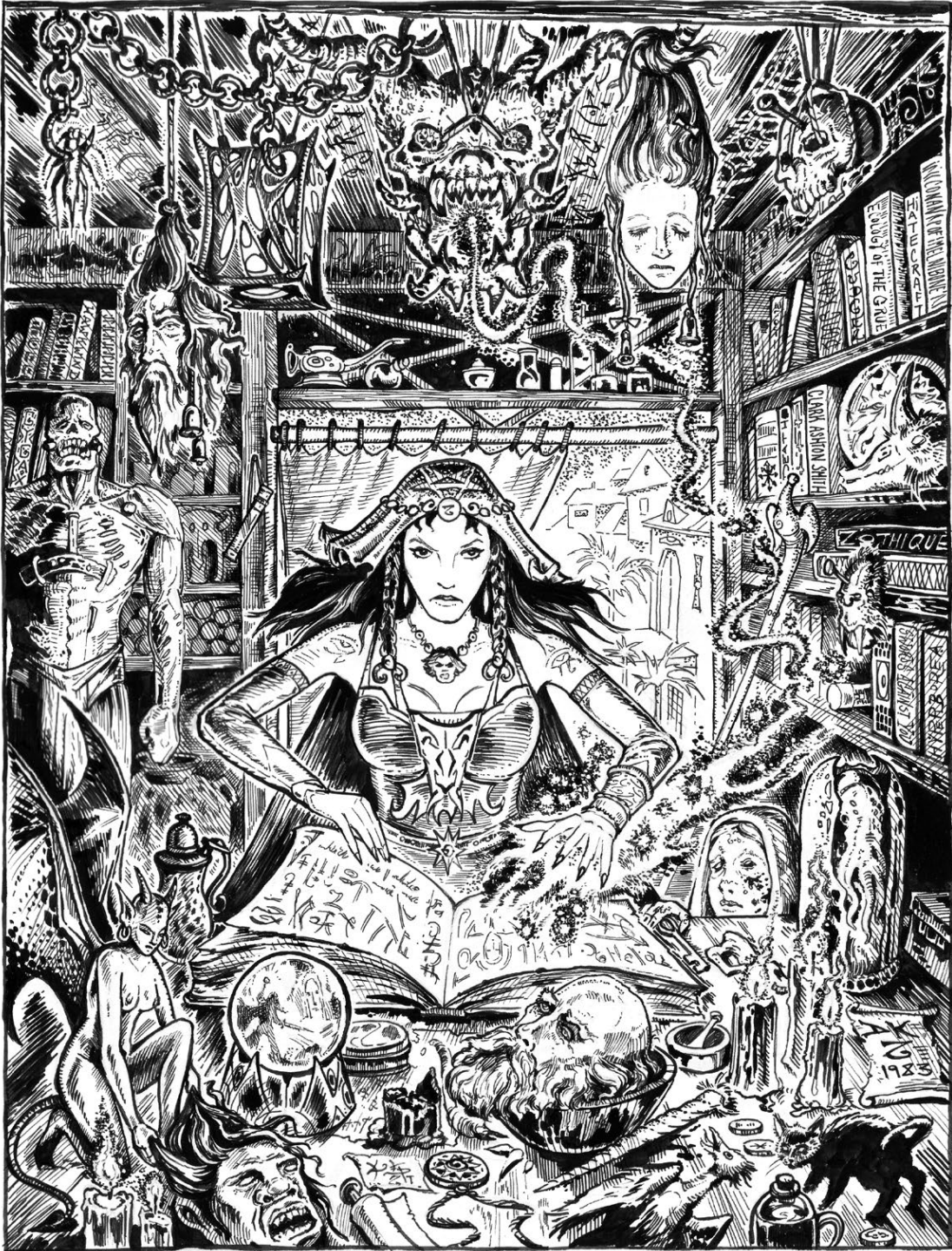

Sword & Sorcery comes to life on every page. Artists Jeff Dee, Jeff Easley, Jason Edwards, Tom Galambos, Fredrich Haas, Jim Holloway, Doug Kovacs, Diesel Laforce, William McAusland, Brad McDevitt, Jesse Mohn, Peter Mullen, Russ Nicholson, Erol Otus, Stefan Poag, Jim Roslof, Chad Sergesketter, Chuck Whelon, and Mike Wilson (phew) flood the pages in pulpy goodness.

What is Dungeon Crawl Classics?

Dungeon Crawl Classics, or “DCC” is a cult classic that carries on the spirit of its older predecessor and certified dad: “Advanced Dungeons and Dragons,” which reigned supreme from 1977 through 1983 (and is still played today).

Dungeon Crawl Classics is often lumped with the OSR, a movement, school, and subculture with varying names, like, the “old school revival” or the “old school renaissance.” The distinction is long fought over and beyond this delve. There are thousands of games within the OSR, many of which don’t resemble DCC.

Instead, the more important takeaway is that Dungeon Crawl Classics aims to engender the same wonder and curiosity by drawing from the same well as AD&D: pulp fantasy. The genre made famous by pulp writers like Robert E. Howard, Michael Moorcock, Jack Vance, and H.P. Lovecraft.

In these stories, civilization bob in and out of ruin while heroes fight off fantasy critters, snake people, and cosmic horrors. The gods are fickle, technology is dusty, magic feeds on blood, and humans are out of their depth.

It’s a broad church of horror and fantasy, curiosity and ignorance, camp and gravity, good tastes and poor tastes. It’s a buffet of vibes. Wizards with funny beards included.

Severed heads, tentacled horrors, and occult rituals. Everything a growing pulper needs. These illustrations can be found in the starter rules at Goodman Games.

The challenge of going “old-school.”

The biggest separation between Dungeon Crawl Classics, AD&D, and pulp fantasy is time. Time has allowed the latter to calcify, fossilize, and become part of the fabric of modern fantasy.

The themes and ideas are now the starting point. Nothing is new or mysterious about snakes controlling empires or wizards performing occult rituals. Even the gameplay of Dungeons and Dragons is rote enough to be shorthand comedy for people who otherwise wouldn’t know the game if you said its name.

Surprise and wonder are deader than an ancient empire. The genre and its games have slowly smoothed out in the way raw mountains grind down into comforting hills.

This was not how things started.

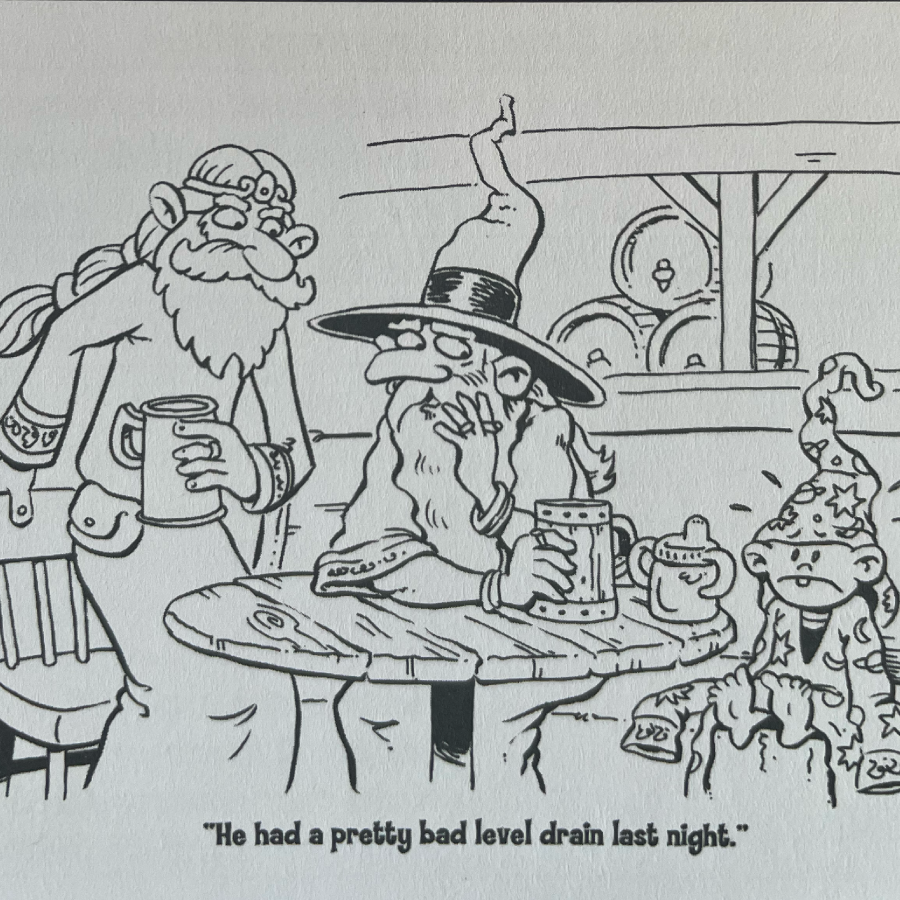

There's a fierce debate about including humor like this in an rpg book. I think for this genre it's mandatory. Two of these are from DCC. The other two are from AD&D. You can spot the latter by the cheaper paper.

Why pulp and AD&D hold the imagination.

In the early days, the twenty-sided die was bought at a school supply store and made into a die. They didn’t come finished. You bought plastic polyhedrons and scribbled the numbers on them with a crayon.

Many of the monsters were third-party toys from Hong Kong. The Owlbear, for example, was a plastic figurine of a “prehistoric creature.” Gary Gygax, co-creator of D&D, called it an “Owlbear” in his games of Chainmail, an early D&D predecessor.

The art in the first D&D books was drawn by untrained artists and high school students (not pejorative). Sometimes they traced artwork from the covers of pulp magazines. The result was a lot of art with an emotional consistency but not a cultural or cogent historical one.

The books were cobbled together on a budget by hobbyists. They were printed, stapled, and distributed at war gaming conventions between friends and classmates. Early writers, like the artists, combined ideas liberally and unceremoniously. As a result, early rpg adventures, characters, and themes matched their pulp inspirations and slammed unlikely ideas together like a Hadron Collider for fiction. Like the popular genres it riffed on, the flash and big idea was the substance.

The hobby was primed to find an audience and keep them guessing. Everything, down to its components, were new, bizarre, and raw. It was unexplainable and limitless.

Many first-time players feel a version of that excitement.

Early in my design and advertising career, I introduced roleplaying games to non-gamers, non-westerners, and non-geeks. The best part was seeing the old bread-and-butter ideas discovered by neophytes. Believe it or not, the twenty-sided die is still alien to many folks. And dungeons? Most outsiders think that means jail. A mythic underworld? Surely not Hades from Disney’s Hercules. Magic? Get out of here, Harry Potter.

This sudden reveal of pulp fantasy and old-school gaming never existed for us grizzled geeks. It was always here. Conquered, repackaged, and optimized. We’ll never feel what it’s like to hover over secret oceans—of which we know nothing.

There might be a secret door, though…

Have you played Dungeon Crawl Classics?

A short break to talk about visual design…

There’s an inherent tension in critiquing visual design. The goal is to examine things on their terms. What are the goals? Does the design achieve that goal? What is the story? Does the design tell that story?

For months, I considered making a laundry list of DCC’s many inexplicable design decisions. Some defy good tastes or any quality control. Things like:

- Removing spaces from sentences. Tosavespace? I’mnotsure. Theyhadplentyofspace.

- Stretching text, slanting it, or squishing it together. Torture on the eyes.

- Using multiple drop caps on one page. It’s not a hard rule, but it is ugly.

- Constantly shifting margins. Narrow gutters. All that with a side of fries.

There are over 500 pages in the Dungeon Crawl Classics rulebook. I'd redesign all of them. Which is why I should never be hired to lay out a DCC book. (Don't worry, 450 of the 500 pages are spells and charts.)

I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Then, one night, while I tossed in a cold sweat. I muttered in my sleep. “Kerning. Leading. Margins. Paper. Pulp.” And that’s when I remembered. All those old books were shit, weren’t they? Are "mistakes " an irreducible part of the genre?

Would fixing the bad font choices, kerning, and design gaffs make it feel false?

I think the answer is yes. Does the lack of polish and craft go too far? Also yes. However, I can’t deny how it plays into my thesis. Maybe the upsetting design decisions are brilliant.

Why Dungeon Crawl Classics persists.

Dungeon Crawl Classics evokes the feeling of Appendix N and the old-school scene, especially in its visual design, mechanics, and community.

Yes, the literal evocations are there. DCC is packed with mustachioed barbarians in bell bottoms. And once in a blue moon, I must endure Baywatch elves holding staves like shake weights (though these gaffs are rarer and rarer). Even the delightful self-referential gag comics of the original AD&D books make an appearance. It’s all there. The good, the bad, and the old-school.

But inclusion is not what makes Dungeon Crawl Classics feel alive. It’s the way it is deployed. DCC has figured out how to make these things feel new again by taking everything and reflecting it in a funhouse mirror.

It dials everything to 11 to recreate the ecstatic truth pure clones cannot. The result is a look and feel that’s indistinguishable from the real thing.

Today, if you want to play DCC, you need dice many hobby shops don’t stock. Is it the same as inventing a d20? No, but there is a palpable sense of wonder generated by the d30. Gone is the age of misshapen d20s. Now is the age of the d17—an obtuse little polyhedron with even weirder math and angles. And this is just the start of DCC’s many hat tricks: a shred of the old lives on in the new.

All the tenets of playing AD&D for the first time are weirder, bigger, and more counter-culture than before. Did Gary Gygax’s obsession with tables capture your imagination? Good news, this game has more. Did you like pulling out an obscure rule for every situation? Good news, DCC has bespoke rules written into half of its modules. Do you love funhouse dungeons, weird little guys, and chaos? Good news, DCC makes it impossible to miss. Do long for the age when D&D was advertised on corkboards with funky photocopied ads? Good news, the back of the book is plastered with them like an old yearbook.

For a long time, I didn’t like Dungeon Crawl Classics. From the outside looking in, it looked like another old-school game sticking to its culture like an Orthodox zealot. You know the type, the gamer who thinks whitespace in a book is “ugly.” Or one who screams woke when you ask them for pronouns.

I unfairly saw the cover of DCC and thought, “Here are folks who have no interest in doing something new. They’ll cling to the past, even if the past was merely a workaround.”

And then I read it. And I remembered reading an rpg for the first time. I felt like one of those players I taught. I didn’t understand a lick of it. They were doing something new. But they were doing it to summon something old. The bad typography was aping bad typography from the pulps. The cobbled rules were intentional. The camp, schlock, and grit were the goal.

Dungeon Crawl Classics aims to recreate the old-school spirit.

And the truth is, they did.